Notes-React

Topics

- React Introduction

- What is React

- React vs Vue vs Angular

- How to create React application and file structure

- React Features

- Virtual Dom

- SPA,JSX,Bebel

- One way data binding

- Components

- Class Components

- Functional component

- Named and default export

- Communiny support

- Web and mobile

- Class and functional component

- Components and props

- Is there any reason to still use react class components?

- Functional components vs class components in react

- Migrate class components to functional components with Hooks in react

- State and Props

- How to use props

- Pass props in both class and functional component

- How to update state from props

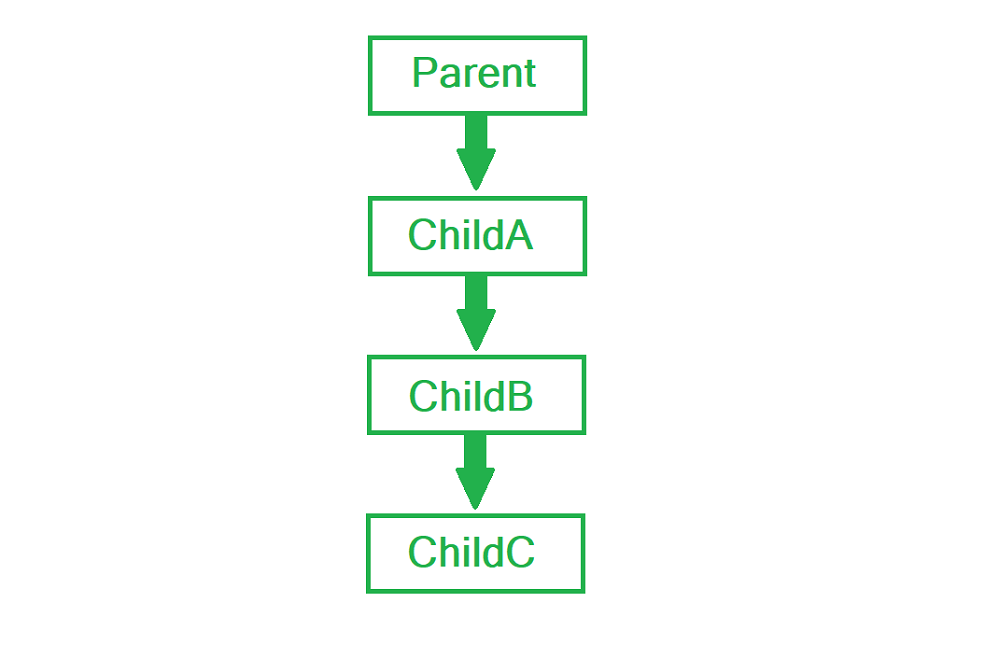

- How to pass data from parent to child and vice versa

- Putting props to usestate

- Conditional rendering

- How to perform

- Different techniques for conditional rendering

- Rendering

-

@Mounting constructor() render() componentDidMount() @Updating shouldComponentUpdate() render() componentDidUpdate() @Unmounting componentWillUnmount()

-

- Lists and keys

- List components in react

- Why do we need the key props”

- Events Handling events in react

- Synthetic events

- React event handler

-

HOOKS

- UseState

- useEffect

- useRef

- React.memo()

- useMemo

- UseCallback

- useReducer

- useParams hook

- How to make Custom Hooks

-

- How to perform routing

- Brower router

- Routes

- Route

- Link

- Dynamic params in Routing

- useNavigate

- useLocation

- Props drilling

- State uplifting

- Axio Vs Fetch

- Get, post, put,delete

- Fetch json file and show it in the screen

- Create own API and Fetch it and show on the screen

- Difference between axio and fetch

- State management

- REDUX Toolkit

- perform CURD operation in redux

- Redux thunk

- Redux saga vs Thunk

REACT NOTES

DAY-1

What is React.JS?

-

React.js is a popular open-source JavaScript library used to build user interfaces for web applications. It was developed by

Facebookand has been widely adopted by the web development community for its simplicity, speed, and flexibility. -

In a nutshell, React allows developers to create reusable UI components that can be combined to form complex user interfaces. Each component encapsulates its own logic and state, making it easier to reason about the behavior of the application.

- React is based on a concept called the virtual DOM, which is a lightweight representation of the actual DOM (Document Object Model).

- When a user interacts with a React component, the virtual DOM is updated to reflect the changes, and then React efficiently updates only the necessary parts of the actual DOM to reflect those changes. This results in better performance and a smoother user experience.

There are two kinds of programming,

- Declarative Programming

- Imperative Programming

Declarative Programming:

Its main goal is to get desired output without describing how to get it .

Imperative Programming:

Its main goal is to describe how to get output or accomplish it

React is Declarative in nature.

- Finally, React can be used with other popular front-end libraries and frameworks, such as Redux for managing state and React Router for routing. It also has a large and active community, which provides helpful resources and support for developers.

React Vs Angular Vs Vue

| Feature | React | Vue | Angular |

|---|---|---|---|

Created by |

Evan You | ||

Initial Release |

2013 | 2014. | 2010 |

Architecture |

Component-based | Component-based | Component-based |

Learning Curve |

Low | Low | High |

Performance |

High | High. | High |

Data Binding |

One-way | Two-way | Two-way |

Templating |

JSX | Html-based | Html-based |

State Management |

Redux, Context API | Vuex | RxJS, ngrx |

Ecosystem |

Large | Growing | Large |

How to Install and File structure

When you create a new React app using create-react-app, it sets up a default project structure to help you get started quickly. The file structure is designed to organize your code in a scalable and maintainable way. Here’s a brief explanation of the key files and directories:

1. node_modules:

- This directory contains all the dependencies and libraries that your React app requires. You don’t need to manually manage this folder, as it’s created and maintained by npm.

npmstands for Node Package Manager. It’s a library and registry for JavaScript software packages. npm also has command-line tools to help you install the different packages and manage their dependencies.

2. public:

-

This directory contains static assets that don’t need to go through the build process, like images or the

index.htmlfile. index.html:- The main HTML file that serves as the entry point for your React application. It includes a div with the id “root,” where your React app will be rendered.

favicon.ico:- The icon that appears in the browser tab.

3. src (Source Code):

-

This is where your React application’s source code lives.

index.js:- The JavaScript file that is the main entry point for your React application. It renders the root component into the HTML

divwith the id “root” fromindex.html.

- The JavaScript file that is the main entry point for your React application. It renders the root component into the HTML

App.js(orApp.jsx):- The main component of your application. It’s usually the parent component that contains other components.

App.css(orApp.scss):- The styles specific to the

Appcomponent.

- The styles specific to the

index.css(orindex.scss):- Global styles that are applied to the entire application.

4. Configuration Files:

package.json:- Contains metadata about the project, including dependencies, scripts, and other configurations.

package-lock.json:- Lock file that helps ensure that the same dependencies are installed on all machines.

README.md:- A readme file containing information about the project, how to set it up, and other relevant details.

5. public and src Level Files:

public/favicon.ico:- The favicon for your app.

public/manifest.json:- A manifest file that provides metadata about your application, such as its name, description, and icons.

src/serviceWorker.js:- A service worker file used for progressive web app functionality.

src/setupTests.js:- A setup file for running tests.

6. public and src Level Directories:

public/images:- A directory where you can store images.

src/components:- A directory to organize your React components.

src/assets:- A directory for static assets like images, fonts, etc.

7. Hidden Files:

.gitignore:- A file that specifies intentionally untracked files to be ignored by Git.

.env:- An environment variable file for setting environment-specific configurations.

.eslint*and.prettierrc:- Configuration files for ESLint and Prettier, tools used for code linting and formatting.

8. yarn.lock (or npm-shrinkwrap.json):

- Lock files that help ensure consistent dependencies across different environments.

-> Package.json:

The package.json file in a React project contains metadata about the project, including information about its dependencies, scripts, and other configurations. Let’s break down the common dependencies you might find in a typical package.json file generated by create-react-app:

{

"name": "your-react-app",

"version": "0.1.0",

"private": true,

"dependencies": {

"react": "^17.0.2",

"react-dom": "^17.0.2",

"react-scripts": "4.0.3",

"web-vitals": "^1.0.1"

},

"scripts": {

"start": "react-scripts start",

"build": "react-scripts build",

"test": "react-scripts test",

"eject": "react-scripts eject"

},

// ...

}

1. react and react-dom:

- These are the core libraries for building React applications.

reactcontains the functionality for creating and managing React components, whilereact-domprovides methods for interacting with the DOM, such as rendering React components.

2. react-scripts:

react-scriptsis a set of scripts and configurations that abstracts away the complex configuration for build tools like Webpack and Babel. It includes scripts for starting the development server (start), building the production version of your app (build), running tests (test), and ejecting fromcreate-react-appfor more customization (eject).

3. web-vitals:

web-vitalsis a library for measuring web vitals, which are metrics related to the performance and user experience of a web page. These metrics include things like page load time, responsiveness, and visual stability.

4. dependencies Object:

- This section lists the dependencies required for your React app to function. The versions specified with the

^symbol indicate that your app can use newer patch releases (backward-compatible updates) of these dependencies.

5. scripts Object:

- This section defines scripts that you can run using

npmoryarn. Common scripts include:start: Launches the development server.build: Creates a production build of your app.test: Runs tests using the testing framework configured for your app.eject: Ejects fromcreate-react-app, exposing the configuration files for customization.

6. Other Fields:

-

nameandversion: These fields provide information about the name and version of your project. -

private: This field is set totrueto prevent accidental publication of your code as a public package.

7. devDependencies Section (Not Shown):

- When you eject from

create-react-appor add additional packages, you might see adevDependenciessection in yourpackage.json. This section includes packages needed only during development, such as testing libraries, build tools, or code formatting tools.

Remember that the actual content of your package.json might vary based on the tools and libraries you’ve added to your React project. Dependencies can be added using the npm install or yarn add commands, and their versions are typically managed automatically using lock files (yarn.lock or package-lock.json).

React features

1. React: The Virtual Dom

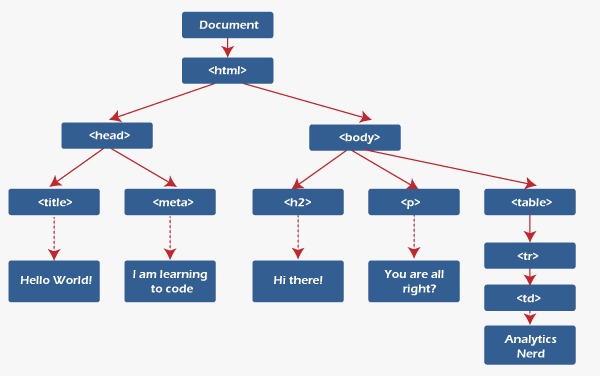

DOM:

DOM stands for Document Object Model. Normally, whenever a user requests a webpage, the browser receives an HTML document for that page from the server. The browser then constructs a logical, tree-like structure from the HTML to show the user the requested page in the client.

This tree-like structure is called the Document Object Model, also known as the DOM. It is a structural representation of the web document as nodes and objects, in this case, an HTML document.

The problem with Dom

DOM manipulation is the heart of the modern, interactive web. Unfortunately, it is also a lot slower than most JavaScript operations. This slowness is made worse by the fact that most JavaScript frameworks update the DOM much more than they have to.

Virtual Dom

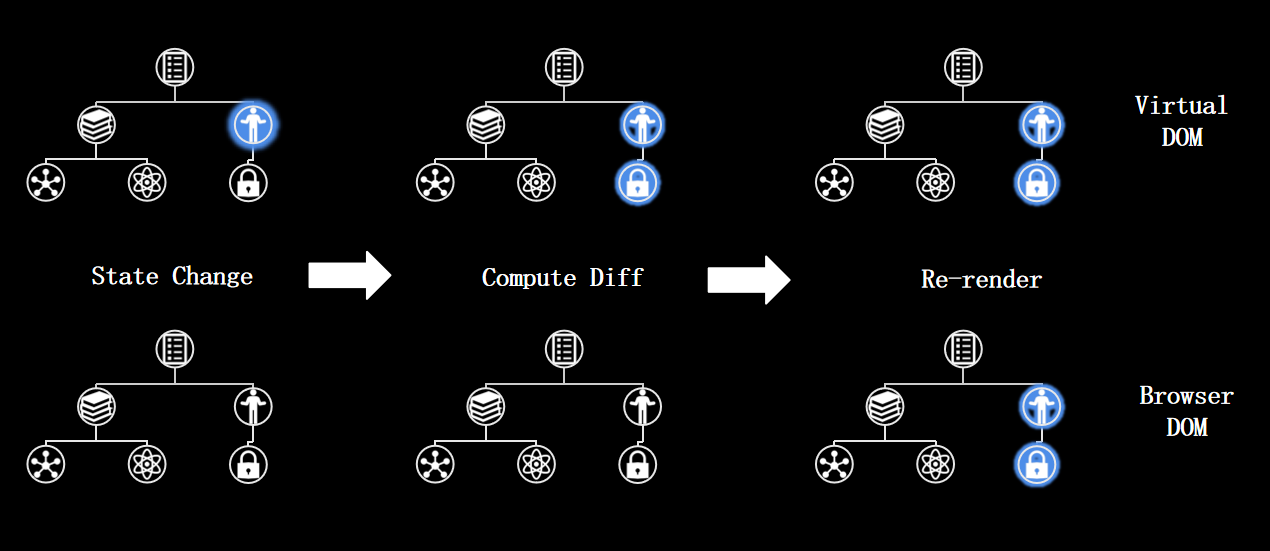

- React contains a lightweight representation of real DOM in the memory called Virtual DOM.

- DOM gets created whenever any React application gets loaded on the screen for the first time, Whenever React components gets mounted on the screen for the first time.

- Now when any user makes any changes on the screen like button click, then the changes will not directly go to Real Dom.

- So, we are having two virtual doms, one VDOM gets created at the time of mounting of react component so it is a copy of your real DOM.

- Another VDOM is the dom which contains the new changes, updated state variables values.

- Now these two virtual DOMs will get compared with each other and will check for the new changes this complete procedure is known as

diffing algorithm. - Now the new changes will be updated in your Real DOM, this procedure is known as

RecoinciliationThis makes a big difference! React can update only the necessary parts of the DOM. React’s reputation for performance comes largely from this innovation.

In summary, here’s what happens when you try to update the DOM in React:

- he entire virtual DOM gets updated.

- The virtual DOM gets compared to what it looked like before you updated it. React figures out which objects have changed.

- The changed objects, and the changed objects only, get updated on the real DOM.

- Changes on the real DOM cause the screen to change.

2. SPA

-

A single-page application (SPA) is a type of web application that loads a single HTML page and dynamically updates the content as the user interacts with the application. In a traditional web application, clicking on a link or submitting a form would typically result in a request to the server, which would respond with a new HTML page to be rendered in the browser. In contrast, a SPA loads all the necessary HTML, CSS, and JavaScript files upfront and then communicates with the server in the background to fetch or update data as needed.

-

React is a popular JavaScript library for building SPAs. React allows developers to create reusable UI components that can be composed together to create complex user interfaces. React components are declarative, meaning they describe what should be rendered on the page rather than how it should be rendered. This makes it easier to reason about the code and to make changes without introducing bugs.

-

In a React SPA, the initial HTML page typically only contains a single “div” element, which serves as the entry point for the React application. When the page loads, React renders the initial UI based on the state of the application. As the user interacts with the application, React updates the UI in response to events such as button clicks or form submissions.

-

To handle server requests, a React SPA typically uses an API (Application Programming Interface) to communicate with the server. The API provides a set of endpoints that the client-side code can use to fetch or update data. The client-side code sends requests to the server using the Fetch API or other libraries such as Axios or jQuery. When the server responds, the client-side code updates the state of the application and rerenders the UI as needed.

One advantage of using a React SPA is that it can provide a smoother and more responsive user experience compared to traditional web applications, since the page does not need to reload every time the user interacts with it. However, SPAs can be more complex to build and maintain, since they require more client-side code and may require additional server-side infrastructure to support the API.

3. JSX and Babel

JSX is a syntax extension for JavaScript that allows developers to write HTML-like code within their JavaScript code. It was developed by Facebook as part of the React library and is used extensively in React applications.

With JSX, developers can write code that looks like HTML, but is actually a combination of JavaScript and HTML. For example, instead of creating a DOM element using plain JavaScript like this:

const element = document.createElement('div');

element.innerText = 'Hello, world!';

In JSX, the same code can be written as:

const element = <div>Hello, world!</div>;

JSX is not a separate language, but a syntax extension that is transformed into plain JavaScript by a compiler such as Babel.

Babel:

Babel is a JavaScript compiler that allows developers to use modern JavaScript syntax and features while still supporting older browsers that do not support these features. Babel can compile JSX code into plain JavaScript code that can be run in any modern web browser.

In addition to transforming JSX code, Babel can also transform other modern JavaScript features such as arrow functions, template literals, and classes into code that can run in older browsers. Babel does this by analyzing the code and replacing any unsupported features with equivalent code that can be run by older browsers.

Overall, JSX and Babel are important tools in the React ecosystem, allowing developers to write modern, expressive code that can be run on a wide range of web browsers.

4. One Way Binding

-

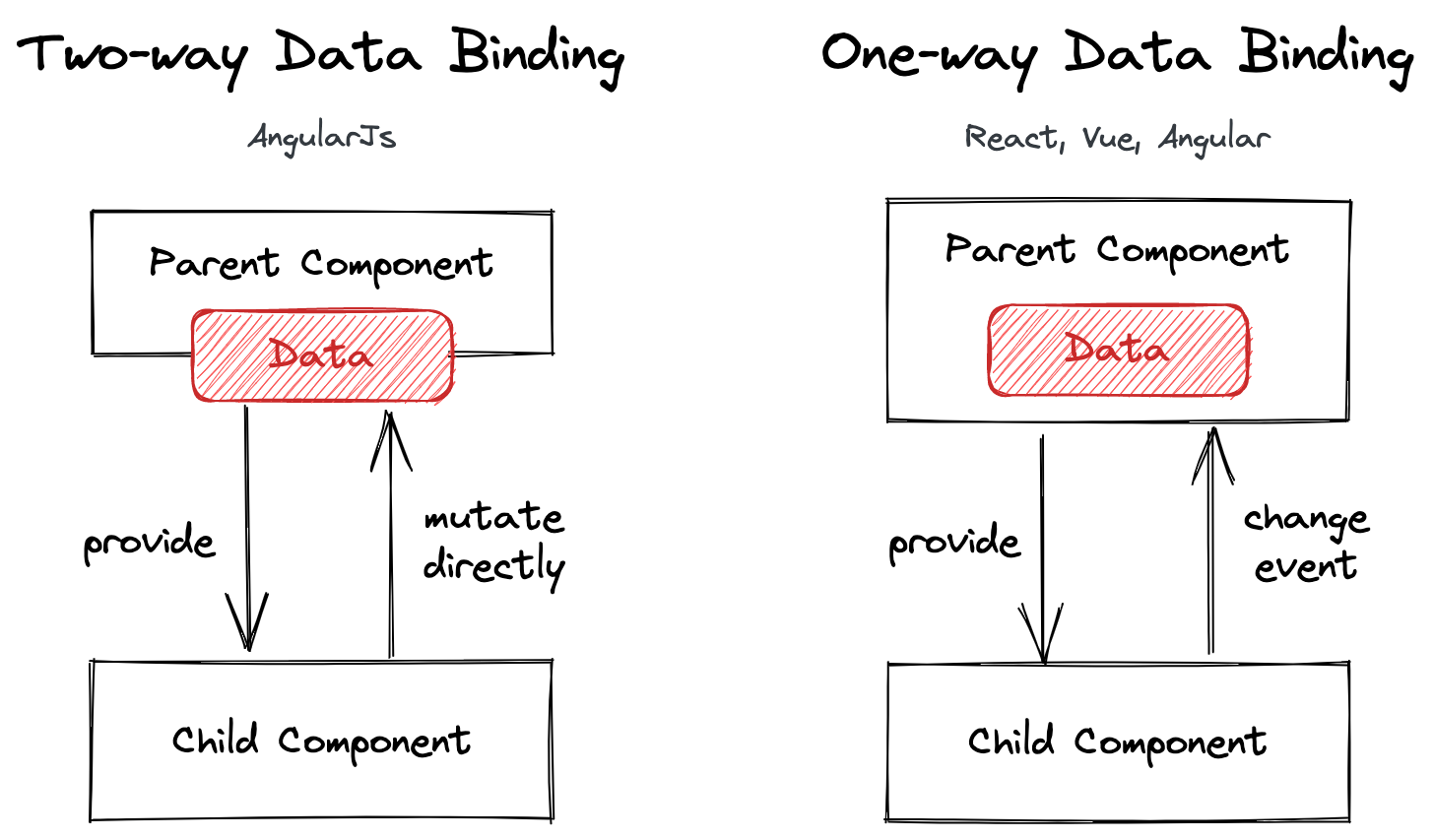

One-way data binding is a data flow mechanism in which the data flows only in one direction, from the data source to the UI element. This means that when the data changes, the UI element that is bound to the data is automatically updated to reflect the new data, but the reverse is not true.

-

In one-way data binding, changes made to the UI element do not update the data source. If the user changes a value in the UI, the change is not automatically propagated back to the data source. Instead, the developer must explicitly update the data source based on the new value in the UI.

One advantage of one-way data binding is that it can simplify the code and reduce the risk of unintended consequences. Since the data flow is unidirectional, it is easier to reason about the code and to track the source of changes. Additionally, one-way data binding can improve performance by reducing the number of updates that need to be made to the UI.

Example:

import React, { useState } from 'react';

function Example() {

const [count, setCount] = useState(0);

return (

<div>

<p>You clicked {count} times.</p>

<button onClick={() => setCount(count + 1)}>

Click me

</button>

</div>

);

}

This is an example of one-way data binding, as the value of count flows from the state variable to the UI element (the paragraph element), but changes made to the UI element do not affect the state variable.

If we were using two-way data binding, we would need to define an event handler for the paragraph element to update the state variable when the user changes the text. However, in one-way data binding, the paragraph element is only used to display the current value of the ‘count’ variable, and does not update the variable when clicked or changed.

5. Component based

- Component-based architecture: React allows developers to build complex UIs by breaking them down into small, reusable components. Each component is responsible for rendering a small part of the UI, and can be composed together to create larger, more complex UIs.

- There are two types of components in React

- Class based components

- Functional based components

6. Named export and default export

A named export allows you to export multiple values from a module, and each of those values can be imported individually by their name. A default export, on the other hand, allows you to export a single value from a module, and that value can be imported using any name.

Here’s an example of a module with named exports:

// math.js

export const add = (a, b) => a + b;

export const subtract = (a, b) => a - b;

In this example, the math.js module exports two functions: add and subtract. These functions can be imported individually like this:

import { add, subtract } from './math.js';

console.log(add(2, 3)); // Output: 5

console.log(subtract(5, 2)); // Output: 3

Note that when importing named exports, you need to use the curly braces and specify the names of the exports you want to import.

Now, let’s take a look at an example of a module with a default export:

// greeting.js

const greeting = name => `Hello, ${name}!`;

export default greeting;

In this example, the greeting.js module exports a single function called greeting. This function can be imported using any name like this:

import sayHello from './greeting.js';

console.log(sayHello('John')); // Output: Hello, John!

Note that when importing a default export, you don’t need to use curly braces and can specify any name for the import.

In summary, named exports allow you to export multiple values from a module, and default exports allow you to export a single value from a module.

7. Community support

React has a significant advantage of community support, which is one of the reasons for its popularity among developers. The React community is very active and passionate about the technology, and there are many resources available to help developers learn and solve problems.

Here are some ways in which the React community provides support:

Documentation: React has comprehensive documentation that is regularly updated with new features and changes. The documentation is clear and easy to follow, making it an excellent resource for both beginners and experienced developers.

Online forums and communities: There are many online forums and communities where developers can ask questions, share knowledge, and discuss best practices related to React. These communities include Stack Overflow, Reddit, GitHub, and more.

Third-party libraries and tools: The React community has created many third-party libraries and tools that can help developers work more efficiently with React. These include libraries for state management, routing, styling, testing, and more.

Conferences and meetups: There are many conferences and meetups dedicated to React, where developers can attend talks, workshops, and networking events. These events provide an opportunity to learn from experts in the field and connect with other developers.

Open-source contributions: React is an open-source project, which means that anyone can contribute to its development. The React community has a strong culture of open-source contributions, and many developers have contributed code, bug fixes, and documentation to the project.

8. Web and Mobile

React is effective for both web and mobile development because it allows developers to write reusable code that can be shared between different platforms.

React Native, a mobile framework built on top of React, allows developers to write mobile applications using the same programming language and development concepts as web applications. This makes it easier for developers to transition between web and mobile development, and to build applications that work seamlessly across both platforms.

Some of the features that make React effective for both web and mobile development include:

Cross-platform compatibility: React’s focus on reusable components and virtual DOM makes it possible to write code that works on both web and mobile platforms. This reduces development time and cost, and makes it easier to maintain code across multiple platforms.

Third-party libraries and tools: The React community has developed many third-party libraries and tools that can be used to build web and mobile applications. These tools include libraries for state management, routing, styling, testing, and more, which can help developers work more efficiently and effectively.

Components

Class Components

In React, class-based components are a type of component that is defined using a JavaScript class. They are an older method of defining components, and have largely been replaced by functional components in modern React development. However, they are still commonly used in legacy code and in some specialized cases.

Class-based components are defined using the class keyword, and they extend the React.Component class. They define a render() method that returns a React element, which describes the UI that should be rendered to the screen.

Here is an example of a class-based component:

import React from 'react';

class ExampleComponent extends React.Component {

render() {

return (

<div>

<h1>Hello, world!</h1>

</div>

);

}

}

In this example, we define a class-based component called

ExampleComponent. It extends theReact.Componentclass and defines arender() method that returns adivelement containing anh1element.

Class-based components have a few advantages over functional components, such as the ability to define state and lifecycle methods. However, they also have some disadvantages, such as being more verbose and harder to understand for beginners.

In general, functional components are preferred for modern React development, as they are easier to write and maintain, and provide better performance. However, class-based components are still a valuable tool in the React developer’s toolbox, and can be useful in some specialized cases.

what is constructor and super key word?

constructor are used for 2 purposes :

In React class components to initialize the component’s state and to bind event handlers.

super() is used to call the constructor of its parent class. If we would like to set a property or access this inside the constructor we need to call super() method.

It is not necessary to have a constructor in every component.

It is necessary to call super() within the constructor. To set property or use ‘this’ inside the constructor it is mandatory to call super().

React Component with Constructor

import React from 'react';

import ReactDOM from 'react-dom';

class Main extends React.Component {

constructor() {

super();

this.state = {

planet: "Earth"

}

}

render() {

return (

< h1 >Hello {this.state.planet}!</h1>

);

}

}

ReactDOM.render(<Main />, document.getElementById('root'));

output:

Hello Earth

This is a very basic example, but it demonstrates how the constructor and super keywords are used to initialize a React class component’s state.

React Component without Constructor

import React from 'react';

import ReactDOM from 'react-dom';

class Main extends React.Component {

state = {

planet: "Mars"

}

render() {

return (

< h1 >Hello {this.state.planet}!</h1>

);

}

}

ReactDOM.render(<Main />, document.getElementById('root'));

output:

Hello Mars!

Functional component

In React, function-based components are a newer and more lightweight way to define components than class-based components. They are defined using JavaScript functions and can be considered as pure functions that take in props and return a React element.

Here is an example of a function-based component:

import React from 'react';

function ExampleComponent() {

return (

<div>

<h1>Hello World!</h1>

</div>

);

}

In the below example i initialize some values with the help of variable.

import React from 'react';

const FunComp = () => {

const count=0;

const name="SP";

const arr=[1,2,3,4,5];

return (

<>

<div>WELCOME!</div>

<h1>{count}</h1>

<h1>{name}</h1>

<h1>{arr}</h1>

</>

);

}

export default FunComp;

In React, JavaScript objects cannot be directly rendered within JSX because JSX can only render primitive data types like strings, numbers, or arrays. If you want to render the content of an object, you need to access its properties or convert the object to a string using a method like JSON.stringify.

Heres how you can render an objects properties or the whole object as a string:

Render object properties:

If you want to access and render specific properties of the object, you can do it like this:

import React from 'react';

const FunComp = () => {

const obj = { name: "sp" };

return (

<>

<div>WELCOME!</div>

<h1>{obj.name}</h1> {/* Rendering the name property */}

</>

);

}

export default FunComp;

Render the entire object as a string:

If you want to render the entire object as a string (useful for debugging or displaying data), use JSON.stringify:

import React from 'react';

const ClassComp = (props) => {

const obj = { name: "sp" };

return (

<>

<div>ClassComp, {props.name}, {props.age}</div>

<h1>{JSON.stringify(obj)}</h1> {/* Convert the object to a string */}

</>

);

}

export default ClassComp;

In this case, JSON.stringify(obj) will display the object as a string like {"name":"sp"}.

Function-based components have several advantages over class-based components:

-

They are simpler and more lightweight than class-based components, which makes them easier to read, write, and maintain.

-

They are less verbose than class-based components, which means less boilerplate code.

-

They are easier to test because they are just plain functions that take in props and return a React element.

-

They are faster than class-based components, because they don’t have the overhead of a class instance and lifecycle methods.

In summary, function-based components are a simpler and more lightweight way to define components in React. They are easier to read, write, and maintain, and provide better performance than class-based components. For these reasons, they have become the preferred way to define components in modern React development.

Q. Is there any reason to still use react class components?

Yes, there are still some reasons to use React class components, although function components are now the preferred way of writing components in React.

Here are a few reasons why you might still choose to use React class components:

-

Legacy Codebase: If you are working on a legacy codebase that uses class components, it might be more efficient to continue using class components rather than rewriting all of your code.

-

Lifecycle Methods: React class components have access to a number of lifecycle methods that are not available to function components. If you need to use one of these lifecycle methods, such as componentDidMount or componentDidUpdate, you will need to use a class component.

-

More Explicit: Some developers prefer the more explicit nature of class components. With class components, everything is defined in one place, making it easier to see what’s going on in your code.

That being said, function components are generally considered the better choice for new React projects, as they offer better performance, simpler syntax, and easier testing. However, there are still some cases where class components might be the better option.

Functional component Vs Class component

| Functional Components | Class Components | |

|---|---|---|

Definition |

Defined as a JavaScript function | Defined as a JavaScript class |

Stat-Management |

Uses useState and useEffect hooks to manage state and lifecycle methods | Uses state and lifecycle methods inside the class |

Props |

Passed in as an argument to the function | Passed in as a property to the class |

Lifecycle-Methods |

Uses useEffect hook to manage component lifecycle | Has access to lifecycle methods such as componentDidMount and componentDidUpdate |

Performance |

Generally faster because they do not have to create an instance of the component | Slightly slower because they have to create an instance of the component |

Syntax |

Simpler and easier to read and understand | More verbose and complex |

Code-Reusability |

Can be easily reused in other components | Cannot be easily reused in other components |

Testing |

Easier to test because they are pure functions | More difficult to test because they have state and lifecycle methods |

Refs |

Cannot use refs directly inside the component | Can use refs directly inside the component |

DAY-2

State and Props

State:

- In React, a “state” is an object that represents the internal data of a component. It is used to manage the component’s dynamic behavior and to render the component with updated information.

-

The data is passed within the components only.State can be modified. State can be used only in class component.

-

State can be changed by using the setState() method, which is provided by the React framework. When a component’s state changes, React automatically re-renders the component with the updated information.

-

State is typically used to handle user input, control component behavior, and store component-specific data.

- It’s important to note that state is meant to be used only within the component it belongs to. It should not be passed down to child components as props, as this can make the code harder to maintain and debug.

Props:

-

React is a component-based library that divides the UI into little reusable pieces. In some cases, those components need to communicate (send data to each other) and the way to pass data between components is by using props.

-

“Props” is a special keyword in React, which stands for properties and is being used for passing data from one component to another.

-

But the important part here is that data with props are being passed in a uni-directional flow. (one way from parent to child)

-

Furthermore, props data is read-only, which means that data coming from the parent should not be changed by child components.

Props in class component

In a class component in React, props can be accessed via the this.props object. Here’s an example of how to use props in a class component:

#Greeting.js

import React from 'react';

class Greeting extends React.Component {

render() {

return <h1>Hello, {this.props.name}!</h1>;

}

}

export default Greeting;

In this example, the Greeting class extends React.Component and defines a render method that returns a greeting message with the value of the name prop passed to it.

When the Greeting component is used in another component, the name prop can be passed as an attribute, like this:

#App.js

import React from 'react';

import Greeting from './Greeting';

class App extends React.Component {

render() {

return (

<div>

<Greeting name="Alice" />

<Greeting name="Bob" />

</div>

);

}

}

export default App;

In this example, the App class extends React.Component and renders two instances of the Greeting component, each with a different name prop passed to it. When the Greeting component is rendered, it accesses the value of the name prop via this.props.name and uses it to render the greeting message.

Props in functional component

Here’s an example of how to use props in a functional component:

#Greeting.js

import React from 'react';

function Greeting(props) {

return <h1>Hello, {props.name}!</h1>;

}

export default Greeting;

In this example, the Greeting component is a simple functional component that receives a name prop and uses it to render a greeting message.

When the Greeting component is used in another component, the name prop can be passed as an attribute, like this:

#App.js

import React from 'react';

import Greeting from './Greeting';

function App() {

return (

<div>

<Greeting name="Alice" />

<Greeting name="Bob" />

</div>

);

}

export default App;

In this example, the App component is rendering two instances of the Greeting component, each with a different name prop. When the Greeting component is rendered, it will receive the name prop as an argument to its function, and the value of the name prop will be used to render the greeting message.

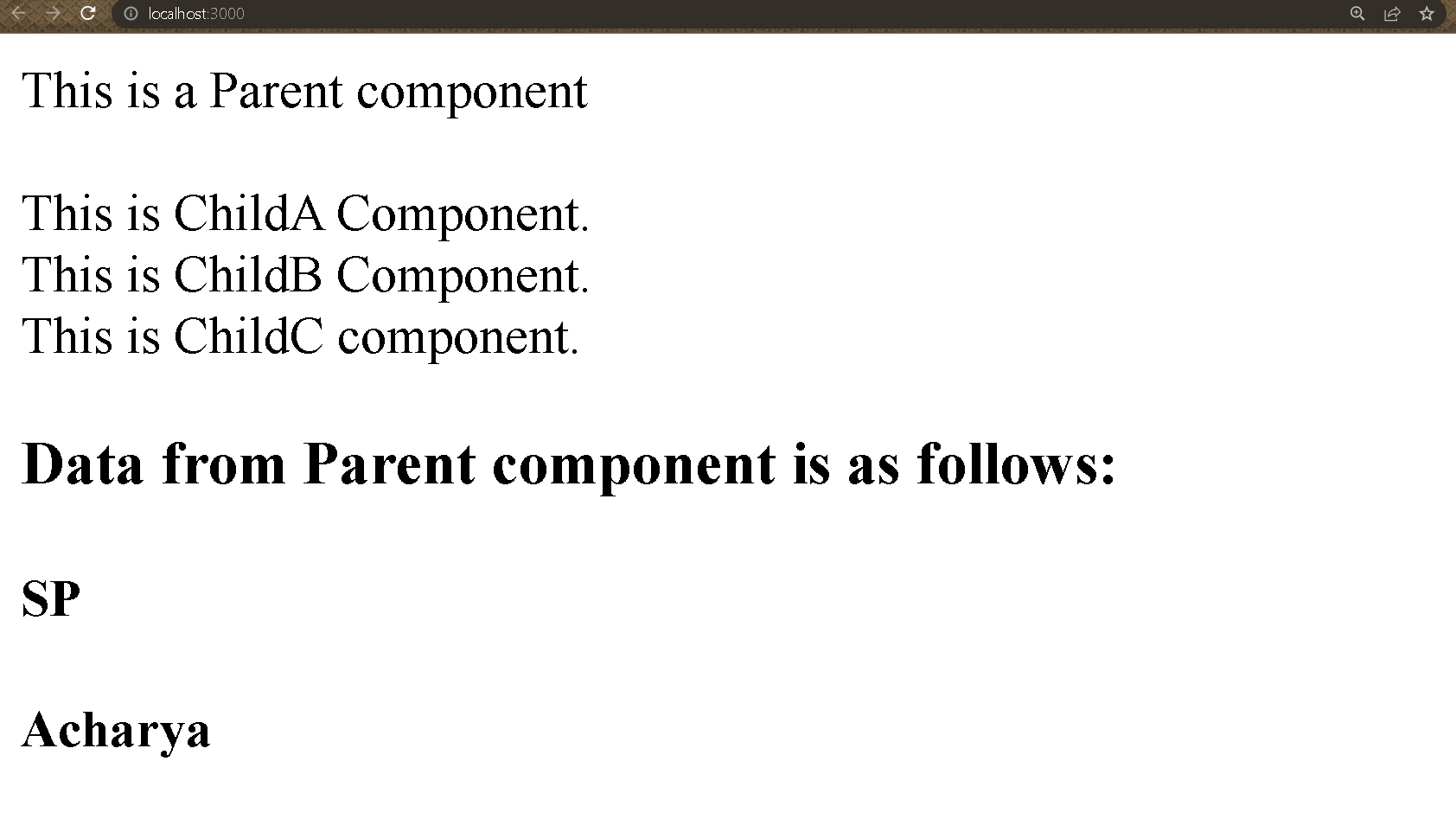

How to pass data from parent to child through Props ?

In React, you can pass data from a parent component to a child component using props.

#Parent Component:

import React from 'react';

import ChildComponent from './ChildComponent';

function ParentComponent() {

const data = {

name: 'John Doe',

age: 25,

city: 'New York',

};

return (

<div>

<ChildComponent data={data} />

</div>

);

}

export default ParentComponent;

#Child Component:

import React from 'react';

function ChildComponent(props) {

const { data } = props;

return (

<div>

<p>Name: {data.name}</p>

<p>Age: {data.age}</p>

<p>City: {data.city}</p>

</div>

);

}

export default ChildComponent;

Output:

In this example, the ParentComponent passes the data object to the ChildComponent as a prop. The ChildComponent then receives the data object as a prop, and can access its properties using dot notation (data.name, data.age, data.city) within the function body.

In this example, the ParentComponent passes the data object to the ChildComponent as a prop. The ChildComponent then receives the data object as a prop, and can access its properties using dot notation (data.name, data.age, data.city) within the function body.

Difference between State and Props

| Property | State | Props |

|---|---|---|

Source |

Defined and managed within a component | Passed from a parent component to a child |

Mutability |

Mutable and can be changed within a component | Read-only and cannot be modified |

Ownership |

Owned by the component that defines it | Owned by the parent component |

Usage |

Used to manage data within a component | Used to pass data down the component tree |

Updates |

Changes trigger a re-render of the component | Changes trigger a re-render of the component |

DefaultValues |

Must be initialized by the component itself | Can have default values defined by the parent |

Scope |

Should only be accessed and modified within component | Can be accessed by child components |

Update State and props using class component

- Updating State:

- To update the state, you need to call the

setStatemethod. - setState method accepts an object that contains the new values of the state properties you want to update.

- It’s important to note that setState is asynchronous, so you should not rely on the current state or props values when updating state.

Here’s an example:

class MyComponent extends React.Component {

constructor(props) {

super(props);

this.state = {

count: 0,

};

}

handleClick = () => {

this.setState({ count: this.state.count + 1 });

};

render() {

return (

<div>

<p>Count: {this.state.count}</p>

<button onClick={this.handleClick}>Increment</button>

</div>

);

}

}

- Updating Props:

- Props are read-only and cannot be directly modified by the component that receives them.

- However, you can pass new props to a component by re-rendering it with new prop values.

- To update props, you need to call the

setStatemethod of the parent component that passed the props to the child component. - When the parent component updates its state, it triggers a re-render of the child component with the new prop values.

Here’s an example:

class ParentComponent extends React.Component {

constructor(props) {

super(props);

this.state = {

name: "John",

};

}

handleClick = () => {

this.setState({ name: "Mary" });

};

render() {

return (

<div>

<ChildComponent name={this.state.name} />

<button onClick={this.handleClick}>Change Name</button>

</div>

);

}

}

function ChildComponent(props) {

return <p>Hello {props.name}</p>;

}

In summary, to update state, you call the setState method with the new state values. To update props, you update the parent component’s state, which triggers a re-render of the child component with the new prop values.

Update State and props using functional component

1. Update State:

- To update state in functional components, you need to use the useState hook provided by React.

- The useState hook returns an array with two values: the current state value and a function that can be used to update the state value.

- To update the state value, you call the function returned by the useState hook with the new state value.

Here’s an example:

import React, { useState } from "react";

function MyComponent() {

const [count, setCount] = useState(0);

const handleClick = () => {

setCount(count + 1);

};

return (

<div>

<p>Count: {count}</p>

<button onClick={handleClick}>Increment</button>

</div>

);

}

2. Updating Props:

To update props from a parent component to a child component in React, the common pattern is that the parent passes props down to the child, and if the child needs to update the parent’s state, it can call a function passed from the parent as a prop.

Example of Parent-Child Communication and Updating Props

1. Parent Component (Parent.jsx):

In the parent component, we’ll define some state and a function that updates the state. This function will be passed as a prop to the child component.

// Parent.jsx

import React, { useState } from 'react';

import Child from './Child';

const Parent = () => {

const [name, setName] = useState('John');

// Function to update the name

const updateName = (newName) => {

setName(newName);

};

return (

<div>

<h1>Parent Component</h1>

<p>Current Name: {name}</p>

{/* Passing the name and update function as props to the Child */}

<Child name={name} updateName={updateName} />

</div>

);

};

export default Parent;

2. Child Component (Child.jsx):

In the child component, we will use the props received from the parent. The child can trigger the updateName function to update the parent state.

// Child.jsx

import React from 'react';

const Child = ({ name, updateName }) => {

// This function will be called when the button is clicked

const handleChangeName = () => {

const newName = prompt('Enter a new name:');

if (newName) {

// Call the parent function to update the name

updateName(newName);

}

};

return (

<div>

<h2>Child Component</h2>

<p>Received Name from Parent: {name}</p>

{/* Button to change the parent's name */}

<button onClick={handleChangeName}>Change Parent Name</button>

</div>

);

};

export default Child;

How It Works:

- Parent Component (

Parent.jsx):- Defines a piece of state (

name) with the initial value"John". - The

updateNamefunction is passed to theChildcomponent as a prop. - The

namevalue is also passed as a prop to theChild.

- Defines a piece of state (

- Child Component (

Child.jsx):- Receives

nameandupdateNameas props. - Displays the

namereceived from the parent. - When the “Change Parent Name” button is clicked, it prompts the user to enter a new name, then calls

updateName(newName)to update the parent’s state.

- Receives

Outcome:

- Initially, the parent displays

"John"as the name. - When the user clicks the “Change Parent Name” button in the child component and enters a new name, the parent component updates its state, causing both the parent and child to re-render and display the updated name.

>How to pass data from child to parent?

In React, you can pass data from a child component to a parent component by using callback functions.

- Define a Callback Function in the Parent Component: In the parent component, define a function that will receive data from the child component.

// ParentComponent.js

import React, { useState } from 'react';

import ChildComponent from './ChildComponent';

const ParentComponent = () => {

const [childData, setChildData] = useState('');

// Callback function to receive data from the child

const receiveDataFromChild = (dataFromChild) => {

setChildData(dataFromChild);

};

return (

<div>

<h2>Parent Component</h2>

<p>Data from Child: {childData}</p>

<ChildComponent sendDataToParent={receiveDataFromChild} />

</div>

);

};

export default ParentComponent;

-

Call the Callback Function in the Child Component: In the child component, receive the callback function as a prop and call it when you want to pass data to the parent.

// ChildComponent.js import React, { useState } from 'react'; const ChildComponent = ({ sendDataToParent }) => { const [childInput, setChildInput] = useState(''); const handleChange = (e) => { setChildInput(e.target.value); }; const sendDataToParentOnClick = () => { // Call the callback function with the data sendDataToParent(childInput); }; return ( <div> <input type="text" value={childInput} onChange={handleChange} /> <button onClick={sendDataToParentOnClick}>Send Data to Parent</button> </div> ); }; export default ChildComponent;

In this example, the ParentComponent passes the receiveDataFromChild function to the ChildComponent as the prop sendDataToParent. When the user enters data in the input field in the ChildComponent and clicks the button, the sendDataToParentOnClick function is called, and it invokes the callback function provided by the parent, passing the data from the child to the parent.

Conditional Rendering

- Conditional rendering is a technique in React that allows you to render different content or components based on certain conditions.

- It’s a powerful way to make your components more dynamic and responsive to user input.

import React, { useState } from 'react';

function Example() {

const [showText, setShowText] = useState(false);

const handleClick = () => {

setShowText(!showText);

};

return (

<div>

<button onClick={handleClick}>Toggle Text</button>

{showText && <p>Some text to show when button is clicked</p>}

</div>

);

}

export default Example;

Output:

.png)

-

In this example, we use the useState hook to create a boolean state variable called

showText. The initial value is false, which means the text won’t be shown initially. -

We also define a function called

handleClickthat toggles the value ofshowTextbetween true and false. - In the return statement, we render a button with an

onClickevent listener that calls handleClick when clicked. -

We also use a conditional statement to render the text only when

showTextis true. IfshowTextis false, the text won’t be rendered. - When the user clicks the button, the handleClick function is called, which toggles the value of showText. This causes the component to re-render, and the text will be shown or hidden based on the new value of showText.

Note that the conditional statement used here is a shorthand way to write an if statement. The expression { showText && <p>Some text to show when button is clicked</p> } means “if showText is true, render the <p> element; otherwise, render nothing”.

There are several techniques for performing conditional rendering in React:

- If statements: You can use regular if statements to conditionally render content. For example:

function MyComponent(props) {

if (props.isLoggedIn) {

return <p>Welcome back!</p>;

} else {

return <p>Please log in.</p>;

}

}

- Ternary operator: You can use a ternary operator to create a more concise if/else statement. For example:

function MyComponent(props) {

return (

<div>

{props.isMember ? <p>Welcome, member!</p> : <p>Please sign up.</p>}

</div>

);

}

- Logical && operator: You can use the logical && operator to conditionally render content. For example:

function MyComponent(props) {

return (

<div>

{props.hasData &&

<ul>

{props.data.map(item => <li key={item.id}>{item.name}</li>)}

</ul>

}

</div>

);

}

- Switch statement: If you have multiple conditions to check, you can use a switch statement to conditionally render content. For example:

function MyComponent(props) {

switch (props.status) {

case 'loading':

return <p>Loading...</p>;

case 'error':

return <p>Error: {props.errorMessage}</p>;

case 'success':

return <p>Success!</p>;

default:

return null;

}

}

Conditional rendering in a class component

import React, { Component } from "react";

class ConditionalRenderingExample extends Component {

constructor() {

super();

this.state = {

isLoggedIn: false

};

}

render() {

// Example of conditional rendering

if (this.state.isLoggedIn) {

return <p>Welcome, User!</p>;

} else {

return <p>Please log in.</p>;

}

}

}

export default ConditionalRenderingExample;

In this example, the ConditionalRenderingExample class component has a state property isLoggedIn that is initially set to false. The render method uses an if statement to conditionally render different content based on the value of isLoggedIn. If isLoggedIn is true, it renders a welcome message; otherwise, it renders a login prompt.

You can also use the ternary operator for more concise syntax:

import React, { Component } from "react";

class ConditionalRenderingExample extends Component {

constructor() {

super();

this.state = {

isLoggedIn: false

};

}

render() {

return this.state.isLoggedIn ? <p>Welcome, User!</p> : <p>Please log in.</p>;

}

}

export default ConditionalRenderingExample;

In this case, the ternary operator is used to achieve the same result as the if statement in a more compact way.

DAY-4

Life Cycle Methods

In React, lifecycle methods are special methods that allow you to perform actions at specific stages in a component’s lifecycle. These methods are called automatically by React at different points in the component’s life.

There are three phases in the React component lifecycle: mounting, updating, and unmounting. Each of these phases has its own set of lifecycle methods.

- Mounting: The component is ready to mount in the browser DOM. This phase covers initialization from

The phase covers initialization from

- constructor()

- render()

- componentDidMount()

- Updating: In this phase, the component gets updated by, sending the new props and updating the state from setState()

This phase covers initialization From

The phase covers initialization from

- shouldComponentUpdate()

- render()

- componentDidUpdate()

- Unmounting: In this phase, the component is not needed and gets unmounted from the browser DOM.

The phase covers initialization from

- componentWillUnmount()

Mounting:

The mounting means to put elements into the DOM. React uses virtual DOM to put all the elements into the memory. It has four built-in methods to mount a component namely.

- Constructor()

- render()

- componentDidMount()

Constructor() method is called when the component is initiated and it’s the best place to initialize our state. The constructor method takes props as an argument and starts by calling super(props) before anything else.

import React, { Component } from 'react'

export default class App extends Component {

constructor(props){

super(props)

this.state = {

name: 'Constructor Method'

}

}

render() {

return (

<div>

<p> This is a {this.state.name}</p>

</div>

)

}

}

render()

- The render() function does not modify the component state, it returns the same result each time it’s invoked and is responsible for describing the view to be rendered to the browser window.

- render() is called by React at various app stages, generally when the React component is first instantiated, or when there is a new update to the component state.

Note : render() will not be invoked if shouldComponentUpdate() returns false.

componentDidMount() The most common and widely used lifecycle method is componentDidMount. This method is called after the component is rendered.

import React, { Component } from 'react'

export default class componentDidMountMethod extends Component {

constructor(props){

super(props)

this.state = {

name: 'This name will change in 5 sec'

}

}

componentDidMount() {

setTimeout(() => {

this.setState({name: "This is a componentDidMount Method"})

}, 5000)

}

render() {

return (

<div>

<p>{this.state.name}</p>

</div>

)

}

}

output:

This is a componentDidMount Method

The above example will print This is a componentDidMount Method after 5 sec. This proves that the method is called after the component is rendered.

Updating

This is the second phase of the React lifecycle. A component is updated when there is a change in state and props React basically has five built-in methods that are called while updating the components.

- shouldComponentUpdate()

- render()

- componentDidUpdate()

shouldComponentUpdate() is used when you want your state or props to update or not. This method returns a boolean value that specifies whether rendering should be done or not. The default value is true.

import React, { Component } from 'react'

export default class shouldComponentUpdateMethod extends Component {

constructor(props){

super(props)

this.state = {

name: 'shouldComponentUpdate Method'

}

}

shouldComponentUpdate() {

return false; //Change to true for state to update

}

componentDidMount(){

setTimeout(() => {

this.setState({name: "componentDidMount Method"})

}, 5000)

}

render() {

return (

<div>

<p>This is a {this.state.name}</p>

</div>

)

}

}

componentDidUpdate method is called after the component is updated in the DOM. This is the best place in updating the DOM in response to the change of props and state.

import React, { Component } from 'react'

export default class componentDidUpdateMethod extends Component {

constructor(props){

super(props)

this.state = {

name: 'from previous state'

}

}

componentDidMount(){

setTimeout(() => {

this.setState({name: "to current state"})

}, 5000)

}

componentDidUpdate(prevState){

if(prevState.name !== this.state.name){

document.getElementById('statechange').innerHTML = "Yes the state is changed"

}

}

render() {

return (

<div>

State was changed {this.state.name}

<p id="statechange"></p>

</div>

)

}

}

In the above example, you will notice that first I have initialized the name state inside the constructor method and after that changed state using setState inside componentDidMount method. So basically the name state should be changed from “shouldComponentUpdate Method” to “componentDidMount Method” after 5 seconds but it didn’t change because of shouldComponentUpdate set to false, If you change that true the state will be updated.

componentDidUpdate()

The componentDidUpdate method is called after the component is updated in the DOM. This is the best place in updating the DOM in response to the change of props and state.

import React, { Component } from 'react'

export default class componentDidUpdateMethod extends Component {

constructor(props){

super(props)

this.state = {

name: 'from previous state'

}

}

componentDidMount(){

setTimeout(() => {

this.setState({name: "to current state"})

}, 5000)

}

componentDidUpdate(prevState){

if(prevState.name !== this.state.name){

document.getElementById('statechange').innerHTML = "Yes the state is changed"

}

}

render() {

return (

<div>

State was changed {this.state.name}

<p id="statechange"></p>

</div>

)

}

}

In the above example, I have set the name state to to current state So React will render the name state from State was changed from previous state to State was changed to current state after 5 seconds. Using the conditional checking of the current state with the previous state prevState.name !== this.state.name inside the componentDidUpdate method, we are updating the value of the id statechange to Yes the state is changed .

componentWillUnmount()

If there are any cleanup actions like canceling API calls or clearing any caches in storage you can perform that in the componentWillUnmount method. You cannot use setState inside this method as the component will never be re-rendered.

import React, { Component } from 'react'

export default class componentWillUnmount extends Component {

constructor(props){

super(props)

this.state = {

show: true,

}

}

render() {

return (

<>

<p>{this.state.show ? <Child/> : null}</p>

<button onClick={() => {this.setState({show: !this.state.show})}}>Click me to toggle</button>

</>

)

}

}

export class Child extends Component{

componentWillUnmount(){

alert('This will unmount')

}

render(){

return(

<>

I am a child component

</>

)

}

}

In the above example, I have created a simple toggle button which will show our Child component if the state is set to true.

So after clicking on the button an alert will popup displaying This will unmount The alert will popup because the component is about to be removed from the DOM which in our case is the Child component.

DAY-5

List and keys

1. Lists and Keys:

In React, a list is a collection of elements rendered with a map function. Each element in the list is assigned a unique identifier known as a key. Keys are crucial for React to efficiently update and reconcile the virtual DOM when the list changes.

2. List Components in React:

Let’s consider a scenario where we want to render a list of items in React. We can create a component for the list and map over the items to generate the list dynamically.

List Component Example:

import React from 'react';

const ListComponent = ({ items }) => {

return (

<ul>

{items.map((item) => (

<li key={item.id}>{item.name}</li>

))}

</ul>

);

};

export default ListComponent;

3. Why Do We Need the key Prop:

Purpose of Keys:

- Uniqueness: Keys help React identify which items have changed, are added, or are removed. They should be unique among siblings in the list.

- Reconciliation: React uses keys to optimize the process of updating the virtual DOM. When items in a list change, React can efficiently determine which elements need to be modified, added, or removed.

Example Explained:

Consider a list of items with unique identifiers (IDs) and names:

const items = [

{ id: 1, name: 'Item 1' },

{ id: 2, name: 'Item 2' },

{ id: 3, name: 'Item 3' },

];

In the ListComponent example:

- The

mapfunction is used to iterate over each item in theitemsarray. - Each

lielement has akeyprop set to the uniqueidof the item. - This key allows React to efficiently track changes in the list.

Usage of ListComponent:

import React from 'react';

import ListComponent from './ListComponent';

const App = () => {

const items = [

{ id: 1, name: 'Item 1' },

{ id: 2, name: 'Item 2' },

{ id: 3, name: 'Item 3' },

];

return (

<div>

<h1>List Component Example</h1>

<ListComponent items={items} />

</div>

);

};

export default App;

Key Takeaways:

- Always provide a unique

keyprop when rendering lists in React. - Use a property that remains consistent and unique for each item, such as an ID.

- Keys assist React in optimizing the rendering process and efficiently updating the DOM when the list changes.

DAY-6

Events in react

Event handling essentially allows the user to interact with a webpage and do something specific when a certain event like a click or a hover happens.

When the user interacts with the application, events are fired, for example, mouseover, key press, change event, and so on.

The actions to which JavaScript can respond are called events. Handling events with react is very similar to handling events in DOM elements.

Below are some general events that you would see in and out when dealing with React-based websites:

- Clicking an element

- Submitting a form

- Scrolling page

- Hovering an element

- Loading a webpage

- Input field change

- User stroking a key

- Image loading

DIFFERENCE BETWEEN HTML AND REACT EVENT HANDLING :

React event handling is similar to HTML with some changes in syntax, such as:

React uses camelCase for event names while HTML uses lowercase.

Instead of passing a string as an event handler, we pass a function in React.

Example: In HTML:

<button onclick="clickHandler()">

Clicked

</button>

In React js

<button onClick={clickHandler}>

Clicked

</button>

Also, like in HTML, we cannot return false to prevent default behavior; we need to use preventDefault to prevent the default behavior.

In HTML

<form onsubmit="console.log('clicked');

return false">

<button type="submit">Submit</button>

</form>

In React js

function Form() {

function handleClick(e) {

e.preventDefault();

console.log('Clicked');

}

return (

<form onSubmit={handleClick}>

<button type="submit">Submit</button>

</form>

);

}

Here, e is a synthetic event. React events do not work exactly the same as native events. See the SyntheticEvent reference guide to learn more.

When using React, you generally don’t need to call addEventListener to add listeners to a DOM element after it is created. Instead, just provide a listener when the element is initially rendered.

Changing state in onClick event listener:

function EventBind() {

const [steps, setSteps] = useState(0);

const clickHandler = () => {

setSteps(steps + 1);

};

return (

<>

<div>{steps}</div>

<button onClick = {clickHandler}> Click </button>

</>

);

}

export default EventBind

Let’s see some of the event attributes:

- onmouseover: The mouse is moved over an element

- onmouseup: The mouse button is released

- onmouseout: The mouse is moved off an element

- onmousemove: The mouse is moved

- Onmousedown: mouse button is pressed

- onload: A image is done loading

- onunload: Existing the page

- onblur: Losing Focus on element

- onchange: Content of a field changes

- onclick: Clicking an object

- ondblclick: double clicking an object

- onfocus element getting a focus

- Onkeydown: pushing a keyboard key

- Onkeyup: keyboard key is released

- Onkeypress: keyboard key is pressed

- Onselect: text is selected

What are synthetic events in ReactJS ?

In order to work as a cross-browser application, React has created a wrapper same as the native browser in order to avoid creating multiple implementations for multiple methods for multiple browsers, creating common names for all events across browsers. Another benefit is that it increases the performance of the application as React reuses the event object.

It pools the event already done hence improving the performance.

e.preventDefault()prevents all the default behavior by the browser.

e.stopPropagation()prevents the call to the parent component whenever a child component gets called.

Note: Here ‘e’ is a synthetic event, a cross-browser object. It is made with a wrapper around the actual event of the browser.

Pure Component

Pure components in React are a type of component that only re-renders when its props or state change. They are also referred to as “stateless components” or “dumb components”. Pure components are a way to optimize the performance of your React application by reducing unnecessary re-renders.

import React, { PureComponent } from 'react'

export default class PureComp extends PureComponent {

constructor(){

super();

this.state={

count:0

}

}

render() {

console.log("Component is called")

return (

<div>

<h1> {this.state.count}</h1>

<button onClick={()=>this.setState({count:this.state.count+1})}>Click</button>

</div>

)

}

}

Higher Order Component

In React, a Higher-Order Component (HOC) is a function that takes a component as an input and returns a new component with additional functionality. Essentially, it’s a way to reuse component logic and share it between different components.

To use a HOC, you simply pass your component as an argument to the function that defines the HOC. The function returns a new component with the added functionality.

So in this below example im going to create one counter and hover counter basically , whenever i hover over the text the counter should be updated by one.

App.js

import React from "react";

import ClickCounter from "./ClickCounter";

import HoverComp from "./HoverComp";

const App = () => {

return (

<div>

<ClickCounter />

<HoverComp />

</div>

);

};

export default App;

ClickCounter.js

import React from "react";

import UpdatedComp from "./UpdatedComp";

const ClickCounter = ({ count, incrementCount }) => {

console.log(incrementCount);

return <button onClick={incrementCount}> Count {count} Times </button>;

};

export default UpdatedComp(ClickCounter);

HoverComp.js

import React from "react";

import UpdatedComp from "./UpdatedComp";

const HoverComp = ({ count, incrementCount }) => {

console.log(incrementCount);

return <h2 onMouseOver={incrementCount}> Hovered {count} Times </h2>;

};

export default UpdatedComp(HoverComp);

UpdatedComp.js

import React, { useState } from "react";

const UpdatedComp = (OriginalComponent) => {

const NewComponent = () => {

const [count, setCount] = useState(0);

const incrementCount = () => {

setCount(count + 1);

};

return <OriginalComponent count={count} incrementCount={incrementCount} />;

};

return NewComponent;

};

export default UpdatedComp;

Output:

.png) So after hovering over the text and click on the button the counter will update by one.

So after hovering over the text and click on the button the counter will update by one.

.png)

In this code, the UpdatedComp function is the higher-order component. It takes a component as its argument and returns a new component with an added state count and a method incrementCount that updates the count. The OriginalComponent is rendered inside the NewComponent, and the count and incrementCount props are passed to it.

Both ClickCounter and HoverComp components are wrapped in the UpdatedComp higher-order component to enhance them with the count state and incrementCount method. Therefore, they have access to the count and incrementCount props, which they can use to update their state and re-render.

In summary, the higher-order component in this code is the UpdatedComp function that takes a component as an argument and returns a new component with added functionality. It is used to enhance the ClickCounter and HoverComp components with state and methods.

DAY-8

HOOKS

-

In React, Hooks are functions that allow developers to use state and other React features in functional components without the need for class components.

-

Hooks were introduced in React version 16.8 to provide a simpler and more flexible way to manage state and side effects in React components.

-

In class component we use different Life cycle methods but in functional components we use hooks instead.

-

Hooks allows to use state and other features without writing a class.

Benefits of using Hooks and Why Hooks was introduced ?

● In react class component, we split our work into different life-cycle methods like componentDidMount, componentDidUpdate and componentWillUnmount, but in hooks, we can do everything in a single hook called useEffect.

● In the class component, we have to use this keyword and also we have to bind event listeners, which increases complexity. This is prevented in react functional components.

There is 2 rules to use Hooks.

-

Only call Hooks at the top level:-<p> Do not call hooks inside loops, conditions or nexted functions. Hooks should always be used at the top level of the react functions.

-

Only call hooks from React functions:- <p> You can’t call hooks from regular js functions instead you can call hooks from React functional component.

There are several types of hooks in React such as:

- UseState

- useEffect

- useMemo

- useRef

- UseReducer

- UseCallback

- useContext

- useParams

- useHistory

UseState

-> usestate hooks allows us to track state in a functional component.<p> -> State generally refers to data or properties that need to be tracking in an application.<p> -> usestate can be used to toggle between 2 values, usually true and false.

How to use it

first we have to import

import {usestate} from 'react'

then inside a function write

const[count.setCount]=usestate(0);

| |

| |

(current (Update the

state) counter's state)

Example

import React ,{useState} from "react";

function App() {

const[Count,setCount]= useState(0);

return(

<>

<h1> count:{Count}</h1>

<button onClick={()=>setCount(Count+1)}>Click</button>

</>

)

}

export default App

In this example, we declare a state variable called count using the useState hook and initialize it to 0. We also declare a function called setCount which will be used to update the count state variable.

MultiCounter Applicarion

import React from 'react'

import { useState } from 'react';

const Function = () => {

const[count,setCount] = useState([0,0])

const increment=(index)=>{

setCount((prevCount)=>{

const newCount = [...prevCount]

console.log(newCount);

newCount[index] += 1

return newCount

})

}

const decrement=(index)=>{

setCount((prevCount)=>{

const newCount = [...prevCount]

newCount[index] -= 1

return newCount

})

}

console.log(count)

return (

<div>

{count.map((counter,index)=>(

<div key={index}>

<h1> count:{counter}</h1>

<button onClick={()=>increment(index)}>increment</button>

<button onClick={()=>decrement(index)}>decrement</button>

</div>

))}

</div>

)

}

export default Function

useEffect

-> The Effect Hook allows us to perform side effects (an action) in the function components. It does not use components lifecycle methods which are available in class components.

-> In other words, Effects Hooks are equivalent to componentDidMount(), componentDidUpdate(), and componentWillUnmount() lifecycle methods.

-> useEffect allows you to run side effects after the component has rendered, and also provides a way to clean up any side effects when the component is unmounted or updated. Here is an example of how to use useEffect:

Side effects have common features which the most web applications need to perform, such as:

- Updating the DOM,

- Fetching and consuming data from a server API,

- subscribing to events.

-> useEffect accepts 2 arguments (callback,[dependency])

The dependency array is passed as the second argument to useEffect, and can contain one or more values. If the array is empty, the effect will only run once, when the component is mounted. If the array contains any values, the effect will re-run whenever one of those values changes.

function App() {

const[Count,setCount]= useState(0);

const [num,setNum]= useState(0);

useEffect(()=>{

alert("clicked")

})

return(

<>

<h1> count:{Count}</h1>

<button onClick={()=>setCount(Count+1)}>Click</button>

<h1> Number:{num}</h1>

<button onClick={()=>setNum(num+1)}>Click</button>

</>

)

}

export default App

Output:

.png)

Here we declare 2 states setCount and setNum. and add counter to both of them . And we use useeffect and alert. so when one user click on the both buttons in every render one alert will appear.

Now lets use empty dependency

useEffect(()=>{

alert("clicked")

},[])

So we just add empty array dependency, now when ever the page is reload for the first time it will show alert. Then whenever we click on both buttons the alert will not popup.

useEffect(()=>{

alert("clicked")

},[num])

Here we pass num state in the dependency.Now when we click on count state button the alert will not popup but whenever we click on num state button the alert will popup everytime we click on the button and simontaniouly the increment will occure.

UseEffect with cleanup method and Api fetching

import React from 'react'

import { useState, useEffect } from 'react';

const Function = () => {

const[data,setData] = useState([])

//componentDidMount(runs once after the initial render)

useEffect(()=>{

console.log("component did mount")

const fetchData= async()=>{

const result = await fetch('https://jsonplaceholder.typicode.com/users')

const json = await result.json();

// console.log(json);

setData(json);

}

fetchData();

//component willunmount

return()=>{

console.log("component will unmount")

}

},[]);

//component DidUpdate (runs on every render,but can be controlled with dependancies)

useEffect(()=>{

console.log(data,"update data")

},[data])//this effect runs ehwnever 'data' chnages

console.log("render")

return (

<div>

<ul>

{data.map(item =>(

<li key={item.id}> {item.name}</li>

))}

</ul>

</div>

)

}

export default Function

The useEffect hook is crucial in React for managing side effects in functional components. A side effect refers to anything that affects something outside the scope of the function, such as fetching data, updating the DOM, or setting timers. The useEffect hook runs after every render by default, but it can also be controlled to run only when specific values change, making it highly useful for various scenarios.

Here are some unique and good examples of using the useEffect hook:

1. Fetching Data from an API

Fetching data from an external API is one of the most common use cases for useEffect. The hook helps you trigger an API call when the component mounts, ensuring that data is loaded as soon as the component is rendered.

import React, { useState, useEffect } from 'react';

const DataFetching = () => {

const [data, setData] = useState(null);

const [loading, setLoading] = useState(true);

useEffect(() => {

// Simulate fetching data from an API

fetch('https://jsonplaceholder.typicode.com/posts/1')

.then((response) => response.json())

.then((json) => {

setData(json);

setLoading(false);

});

}, []); // Empty dependency array ensures this runs only once after the initial render

return (

<div>

{loading ? <p>Loading...</p> : <p>Data: {JSON.stringify(data)}</p>}

</div>

);

};

export default DataFetching;

Why useEffect is important here:

- Without

useEffect, the API call would happen every time the component renders, potentially causing an infinite loop. - With

useEffect, the API call happens only once, after the initial render, which makes it efficient and prevents unnecessary network requests.

2. Set and Clear a Timer

This example demonstrates how you can use useEffect to create a timer (e.g., for a countdown or a clock) and clean up the timer when the component is unmounted.

import React, { useState, useEffect } from 'react';

const Timer = () => {

const [seconds, setSeconds] = useState(0);

useEffect(() => {

const interval = setInterval(() => {

setSeconds((prevSeconds) => prevSeconds + 1);

}, 1000);

// Cleanup function to clear the interval when the component unmounts

return () => clearInterval(interval);

}, []); // Empty dependency array ensures this runs only once

return <h1>Timer: {seconds} seconds</h1>;

};

export default Timer;

Why useEffect is important here:

useEffectis used to set up a timer when the component is mounted.- The cleanup function (

return () => clearInterval(interval)) ensures that the timer is properly cleared when the component is unmounted, preventing memory leaks.

3. Update the Document Title Based on State